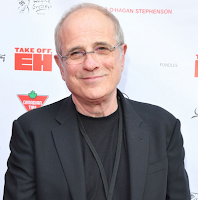

If you’ve lived on planet Earth, it’s highly likely that you’ve encountered the work of the legendary music producer, Bob Ezrin.

Ezrin’s masterful production can be heard on iconic albums such as Pink Floyd’s The Wall and The Division Bell, Kiss – Destroyer, Alice Cooper – School’s Out and Billion Dollar Babies, Peter Gabriel – Car, U2 – Songs of Surrender, and Andrea Bocelli – Si. His work spans decades, shaping the sound of multiple genres and artists.

In addition, throughout his career, Bob has collaborated with a diverse roster of talent, including Lou Reed, Jane’s Addiction, David Gilmour, Kansas, Julian Lennon, The Babys, Tim Curry, Hollywood Vampires, Dr. John, Johnny Reid, and many others. His work with these artists has left an indelible mark on the music world.

Bob was also instrumental in reshaping and making Beth one of Kiss's biggest hits, displaying his knack for transforming ideas into unforgettable music.

In a special feature for The Hamiltonian, we are thrilled to chat with Bob Ezrin, a friend of The Hamiltonian's founder, Cal DiFalco. Here is our conversation with the man who has help shape the soundtrack of countless lives.

1. You’ve described the role of a producer as “part psychologist, part technician, and part dreamer.” In your experience, does the heart of producing lie more in drawing out the artist’s best through trust and atmosphere, rather than prioritizing pure musicality?

The art of Producing is in creating a relationship and environment that inspires and frees the artist to be their best. Musicality naturally follows. Leading from the other direction can result in technically good but artistically less than optimum results.

2. You’ve worked with iconic figures such as Pink Floyd, Alice Cooper, Kiss, Peter Gabriel, and Lou Reed—artists whose music has shaped generations. Does the global impact of your work ever feel surreal? Are there moments when you hear a song you produced on the radio and find yourself transported back to the studio where it all happened, or can you simply enjoy it as a listener?

More often than not, I have forgotten some of the elements in records that I produced and so, hearing them on the radio, often leads to a feeling of discovery. I listen to everything as both a fan and a practitioner. That doesn’t leave a lot of room for wandering back in time. There are some times that I hear something I have totally forgotten about, and when that happens it can trigger a lot of memories. Occasionally I will hear something that catches my ear and think “that sounds great.,.I wonder what it is” only to realize a few seconds later that it’s one of mine. I love those moments.

3. In the studio, how do you recognize when an artist has reached their peak during a session? Is there a moment you look for—an instinct—that tells you, “this is it,” and that any further takes might risk diminishing the magic rather than enhancing it?

It is pretty obvious to me when someone has hit their peak and also when they are flagging. I would think it’s less “instinct” than training and experience that allows me to make these judgements effectively.

4. The Wall* has become one of the most legendary and emotionally complex rock albums in history. What was the most creatively or personally intense moment for you during that project, and how did that experience help shape the final work?

There is no one moment that was the “most creative” or “most intense”. The project was a series of highs and lows, some pretty extreme, that continued over a period of months and months until we had finally built The Wall. During the process, we hit what were new highs and some new and unexpected lows for me, but mostly it was an intensely creative and thrilling time where almost anything was possible because we had all the resources, as much time as we wanted and unfettered imaginations. We were totally free to fly.

5. With home studios, accessible plugins, and increasingly affordable recording tools, how can independent producers and artists guard against overproduction? Do you believe “less is more” still applies in today’s digital age, and what advice would you give to maintain artistic authenticity in such a saturated environment?

I always insist on starting with the basic elements of a new work. I don’t want to start with production. Sometimes, one can start gilding the lily before it becomes a lily. And the flower that is the core of the work, wilts under the weight of it. If you are working in song form, then for me it’s all about the song - the story set to music. And I encourage people to sit down with whatever their instrument is and work out the melody and at least the basic lyrics to the piece before adorning it with production. I think a great song should be performable completely stripped down and still move people. Of course there are compositions that are more about the garden than the individual flower. These are soundscapes that are the bed the song gets planted in. But they are as important as the song itself. And there are some that are built on an instrumental motif - like a synth or guitar riff - where the instrumental hook is as important as the melodic and lyrical one. Whatever the memorable element in the work is, it should be perfected before it is embellished. That’s my opinion.

6. The music industry continues to evolve dramatically—with streaming, AI-generated compositions, and algorithm-driven platforms. From your vantage point, what does the future of true artistry look like? How can artists remain authentic in an increasingly automated world?

Artists always use tools to create. Whether the tool is as simple as language or as complex as Artificial Intelligence, the process is the same: an artist has a feeling or an idea and they need to find a way to express it. If they are painters, they start painting. If they are musicians, they start playing. They start using the available tools to express themselves. At the core of their work is the feeling or idea and for the work to have real validity those must be important and engaging. In the best cases, they are life altering. In the mediocre or worst cases, they end up being irrelevant.

7. If you could revisit one recording session from your storied career—not to change anything, but to relive it for the sheer joy of the moment—what session would it be, and why does it stand out so vividly in your memory?

It would be the sessions when the Beatles recorded She’s Leaving Home or Strawberry Fields - or when the Beach Boys recorded Good Vibrations. These three stand out because those recordings include almost every kind of modern music miracle. And of course, there’s the session when Pink Floyd recorded Comfortably Numb…wait…;-)

Note:

The list of recorded works mentioned above is by no means representative of Bob's entire body of work. He has produced many additional works.

Bob also has a big heart and has made generous contributions to charities of his choosing.

Thanks Bob for the inspiration and the music!

Teresa DiFalco, Publisher-The Hamiltonian

Well done! Great interview a Canadian Icon .

ReplyDeleteWow. Hit this one out of the park. The great Bob Ezrin!!! You lived up to the mystery guest. Are you going to post the answers to the hints? bob, thank-you for the great music. You are #1

ReplyDelete